BREXIT: THE LONG ROAD AHEAD

Oblyon Welcomes Mr. Marco Gianni, Esq. as Chief Marketing Strategist

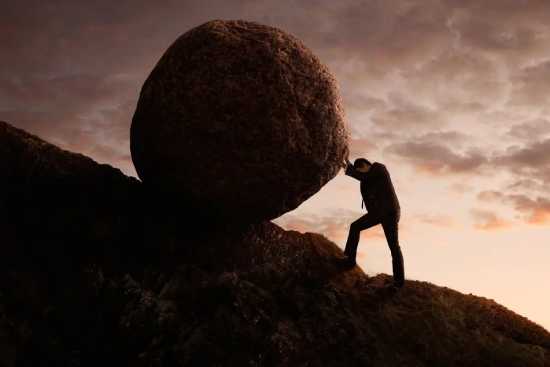

BRUNELLESCHI FILIPPO LAPI, the top manager of the Duomo in Florence

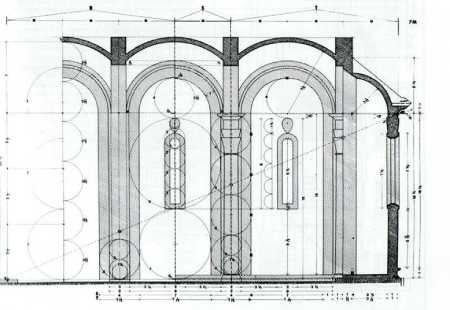

Suspended 50 meters above the ground, amidst a labyrinthine network of ropes, pulleys, and weights, all powered by two determined oxen – you are not part of an ordinary construction site. You are a member of an orchestra of human resilience, daring vision, and sheer innovation. With each twist and turn, bricks, concrete, and diluted wine flasks – in this realm, work safety is no laughing matter – are hoisted and passed along.

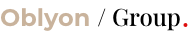

For a decade, you and 85 comrades have traded shifts under the searing sun and biting cold. You’re not just building; you’re forging a symbol that will transcend time and space. The precise «herringbone» pattern you lay, guided by Brunelleschi‘s brilliance, will find its way onto Facebook feeds magically crossing half a millennium time span as if it were a couple of weeks.

True innovation can’t be confined to rigid frameworks or reduced to numerical formulas. It thrives in narratives that stand on a grand vision and true human ambition, defying conventional and myopic wisdom sought by risk-averse and self-glorifying authorities. Bureaucracies cannot produce dreams that turn into realities. There just won’t be any construction, be that physical or spiritual, without a truly human intent, without a pulsing desire for change, unbridled and unconstrained by rules and dogmas. (James C. Scott, «Seeing like a state»).

Any system claiming all-encompassing knowledge is bound to short-circuit. The absence of surprise denies us the thrill of tackling the unforeseen. It kills the power of imagination and dooms us to small incremental and sad changes, mere quantitative steps forward that can be booked and recorded as progress right when they belly the very suppression of human inventiveness. (Rory Sutherland, «The problem with Marxism is too much sense»)

The construction of Santa Maria del Fiore’s dome, orchestrated by Filippo Brunelleschi Lapi, and now brought to life through the majestic digital reconstruction of Margaret Haines’ «Years of the Dome,» unveils the management artistry required to conquer the unknown. (Margaret Haines, «Myth And Management In The Construction Of Brunelleschi’s Cupola«)

An artistry, an elegant movement, a dance almost, jostling between amazing complexities, never seen before, and yet faced head-on. An attitude simply unfathomable in today’s world, where the biggest comfort, the most valuable accomplishment seems to be found in the recoiling from any unknown, from anything that is not well defined and apt to fall under standard, well-rehearsed, and formally approved classification methods. Ledger entry is the new rule of the world.

But reality is stronger than our desire for security and predictability. The more we cling to prefabricated models the more they prove vulnerable precisely to that one random event that escaped and thwarted the omniscience of the all-powerful algorithm, even the one concocted by Nobel-quality minds. The “failed genius” of the LCTM saga still stands to prove and remind us of just that. The global bet on “scientific safety” almost plunged the world into financial annihilation. (When Genius Failed, The Rise and Fall of Long-Term Capital Management).

Challenging Financial Hypernorms: Unveiling the Human Element

The neo-liberal construct of the markets as an emotionless combination of superhighways where raw data are in a state of constant flux enabling rational decisions devoid of any possible human bias proved to be tragically misguided in 1998. At every opening, the markets do not just start from scratch, as if the previous day had never existed.

Sediments of memories, specs of emotions, and human bias of all sorts play havoc with the traders’ minds, with the “humans”. They do remember and act upon their feelings too.

In the end, those feelings proved stronger than the LCTM algorithm. History taught us yet another lesson and yet our urge to escape uncertainty and unpredictability not only persists despite recurrent «system failures,» but seems to be on the increase, leading to the emergence of hypernorms – rigid value systems spanning economic and social realms that need no uncovering of their fictional pretenses and yet, are believed and revered as mystical, divine-like commandments.

Neoliberalism’s portrayal of an optimally efficient market, driven by ever-optimizing individuals bent on a relentless pursuit of their own economic value is the financial version of that architectural hallucination encapsulated in Le Corbusier’s abstract Paris – a dystopic departure not only from reality but from sanity altogether.

How precarious this construct is well shown by the preferences, vehemently expressed, by two groups of volunteers to a British utility’s survey enticing the participants by offering a possible 1.000 GBP windfall on the one hand and a…plastic penguin on the other. The penguin, with a mark-to-market price of 15 “quid”, proved to retain a much higher value than the alternative monetary recompense. A lucky winner who was handed down the “hard cash” demanded the same to be swapped for the penguin. There goes the myth of the Homo Economicus down the drain. (Rory Sutherland, Alchemy, The Surprising Power Of Ideas That Do Not Make Sense)

Yet, modern finance keeps orbiting twin suns: absolute freedom paired with perfect economic auto-determination on the one side and the «shareholder theory» on the other.

The latter functions as a theoretical compass able to rationalize even the incomprehensible and most secretive human behaviors in order to then magically recompose all inconsistencies under an infallible order that can make sense even of….the penguin.

On these pristine and reassuring Cartesian axes, human life unfolds rationally, managed by mathematical indices and alert systems that grapple with any type of risk.

The system can easily spot and discard «zombies» (How to avoid a corporate zombie apocalypse, FT, February 5, 2020), so to make room for innovation as long as the same is cleared by a deluge of legal, fairness, and feasibility opinions that end up building a world of their own, so entangled to suffocate creativity and innovation without securing risk minimization and control. And how could they? Data and signed-off-best practices are inherently backward-looking. All sets of data share a common birthplace: the past. Hence, they cannot safeguard us against the future. (The Wall Street Dilemma, Harvard Business Review)

Unveiling the Thread of Economic Narratives: From Brunelleschi to Starbucks

So immersed in an anesthetized world shy of risk, bent on procedural compliance and personal reputation safeguarding as the ultimate achievement, we naturally tend to suppress and dismiss that natural urge to express our unique human singularity.

That comes at a great cost as a truly functioning and value-creating corporate entity has no chance to materialize without the unbridled spirit of the “homo faber”, the true creator and not the mere life-less proofer, free only to execute a set of pre-arranged objectives.

There can be no economic growth in a corporate landscape that stifles creativity and courage by suppressing human singularity, spontaneity and solidarity for the sake of a “play it safe” attitude that will fail at both generating innovation and insulating us from the risk and incertitude of the future. (Escaping the Fantasy Land of Freedom in Organizations: The Contribution of Hannah Arendt, Yuliya Shymko1 · Sandrine Frémeaux 1,2, Journal of Business Ethics, 2022).

Doubting the system’s self-regulatory efficiency seems not only possible ma plausible and rationale indeed.

A whole array of financial monitoring mechanisms, epitomized by Basel I, II, III, IV – akin to sequels of a Hollywood blockbuster – and by the Bank for International Settlement vouched for Credit Suisse‘s solvency, even as it faced an existential crisis.

The grandest parade of numbers and ratios was put on stage, from LTCR (Long-Term Resilience Rate), HQLA(High-Quality Liquid Asset Rate), and above all, an LCR (Liquidity Coverage Ratio) of 150% (Credit Suisse Group takes decisive action to pre-emptively strengthen liquidity and announces public tender offers for debt securities, Credit Suisse, Ad hoc announcement pursuant to Art. 53 LR): all the capital and risk managing requirements were not only met but exceeded. And yet.

Such skepticism is only compounded by the system knee-jerk-movements that see it passing from relying on an ultra-sophisticated dataset, undecipherable by the layman, to those other indicators made up by the “lattes and macchiatos” dished out by Starbucks, now magically elected to the role of official “pulse” of USA global economy. (Corporate America is over-caffeinated, let us hope our dependence on the fragile US consumer holds up, FT, September 8, 2019).

In that magical and neat dichotomy of «latte makers» and «latte takers,» that makes up the world economy, the Starbucks consumer comes to embody the shifting economic landscape, the real one, the “main street one” (Fed Officials Warn Consumer Is Alone in Carrying U.S. Economy, Bloomberg) and Howard Schultz, a modern-day counterpart to Brunelleschi is the new oracle summoned by the summit of a political power (Howard Schultz Wants to Change the Country With Starbucks | Time Magazine) trying to make sense of things, trying to read the future on the basis of that perfect alternate of caffeinated and decaffeinated offering that comes in all possible varieties of flavor combination so to truly accommodate the human necessity to express its individuality and authenticity adhering to shades of lattes and hair coloring. It’s just magic! (Consumer Society, J. Boudrillard).

From the Brunelleschi Dome’s grandeur to LTCM’s downfall, from the financial crisis of 2008 to the Swiss bank’s fallibility, and from Starbucks’ rise as an economic oracle to the era of neoliberalism and the emancipation of human irrationality – what unites these narratives? A herringbone-like thread stitches these stories across centuries, weaving a tapestry of economic and social evolution within the confines of fleeting lines.

Brunelleschi’s Vision: A Lesson in Governance and Resilience

It all comes together in a single word: Governance.

The essence of governance, as demonstrated by Brunelleschi, intricately complements the tangible herringbone-arranged bricks with an intangible but equally crucial factor. The fusion of tangible and intangible proprietary and distinctive assets forms the heart of a strategy akin to a VRIO value template: valuable, rare, inimitable, organized.

Remarkably ahead of his time by about five centuries, Brunelleschi’s approach predated even the insights of modern consulting giants like McKinsey. (Getting tangible about intangibles: The future of growth and productivity?; McKinsey)

Despite its Renaissance charm, the organization and execution of work during Brunelleschi’s era were anything but romantic or epic. Hierarchical divisions were strict, and worker categories were meticulously regulated – a symphony of roles, titles, and compensations. However, the reality mirrored a contemporary Foxconn assembly line more than the artisan workshops we imagine today.

Nonetheless, Brunelleschi’s brilliance lay in his grasp of a complex system’s efficient functioning. He perceived the absolute interdependence of factors that, when combined, morphed into a distinct unit, transcending simple algebraic sums. No one could claim exclusive ownership of this unique outcome. There was no hierarchy of contribution; every element, in its dynamic unity, forged a new complementarity, birthing transformative value.

The millions of bricks, master masons, and pulleys weren’t mere entries on a balance sheet for cold cost analysis. They defied reduction to numerical efficiency; their value couldn’t be assessed solely on paper or a screen.

Could a Ligurian master be replaced with a Tuscan one due to lower costs?

In the time of the Opera, the «ICT«, Information Communication Technology, that facilitated modern integrated value chains didn’t exist. Today’s shift towards reshoring (Rana Forhoorar, Homecoming, the path to prosperity in a post-global world) not only acknowledges pandemic-induced managerial vulnerabilities but also dismantles that offshoot of neoliberal theoretical efficiency by which all connections and intertwining between economic development and geographical location can be scissored, simply disposed of, in the name of an overarching and self-implementing value maximizing logic. Another Le Corbusier-like-Paris. A dystopian vision embedded in a solemn and barren, lifeless grandeur. (After Neoliberalism All Economics Is Local, Rana Forohar, Foreign Affairs)

Driven by numerical efficiency, the relationship between humans and territory, that intrinsic «embeddedness» (Il segreto italiano, Treccani) vital for the financial sustainability and resilience of both companies and their communities (A return to 1970s stagflation is only a broken supply chain away, FT), has decimated entire communities (A system in crisis: can capitalism survive? The university of Chicago booth, YouTube) and would have quite likely prevented the building of the Dome.

But fortunately, Brunelleschi’s legacy is still standing tall and reminds us of the vital interconnectedness between people and the land they inhabit, a lesson now echoed by the resurgence of local-centric economics.

Unveiling the Essence: The Intertwining of Material and Immaterial in the Renaissance

The interplay between the tangible and intangible, humans and their surroundings, emerges vividly from insights garnered from studies surrounding the Opera, now accessible through Haines‘ digital reconstruction:

(And the Formlessness, Finally, Takes Shape… Studies around Santa Maria del Fiore in memory of Patrizio Osticresi, edited by Lorenzo Fabbri Annamaria Giusti)

Yuri Biondi’s «The Firm As An Entity: Management, Organisation, Accounting, paper 46, University of Brescia,» outlines the «accountant» version of the Dome’s essence.

This essence of an organization, of a corporate entity lies within the specific «intent» around which all factors—both tangible and intangible—organize: «….This new intentional constituent doesn’t merely create an entity as an association of independent resource owners. It shapes the whole wherein functioning constituents make the activity of becoming the whole distinct from the mere sum of interplaying parts…«

A perpetual journey of becoming, an uninterrupted progression propelled by a shared and participatory «intent«: this is the throbbing pulse that has to run through the veins of corporate organization in order to turn them into real value creators and not just more or less well-organized assembly of people and things.

Without the added value of gratuitous participation, supported by a robust foundation of genuine trust, there will always be a looming risk of optimization for the distant past without even realizing it.

The skeptics will only have to consider the enduring architectural «landmark» that spans five centuries, a quite tangible testament to shared intent. The hard-core skeptics will be comforted by «best practices» with an operational record spanning around 20 million years—the tenure of the «bees» on planet Earth. Their shared intent presents pure short-term financial metrics and blind adherence to uniform behavior both granting immediate comfort for the present, and perilous for the future.

Do you think Is just a fairy tale financial theory? Think again.

IBM’s unraveling offers a cautionary and very much down-to-earth saga.

It was precisely a lack of innate system-wide balancing tension that couldn’t save it from corporate bureaucracy, lack of foresight, and ultimate decline.

The Homo Economicus paradigm failed to gauge the trade-off with the tech giant: “my obedience and full compliance for a life of…job security”.

If employees had sensed and reported the winds of innovation, the advent of the desktop, perhaps the once-monolithic IBM would’ve veered course, as their voices transformed a Top-Down culture into a Bottom-Up melody.

But conformity and psychological bunking in the “it’s not my job” attitude are much more appealing and easier than coming to terms with the need to scan the horizon for your own good. A company culture that fosters and nourishes such a mentality, such a stance on life will not only benefit its employees but its very survival to the advantage of the ultimate and true beneficiary of the entire corporate construct according to that very ideology that champions the logic of cold numbers as the one and only True North: the stockholder (Wall Street, an Oliver Stone Movie).

In the grand tapestry of history, Brunelleschi’s dome and the industrious bees illuminate a profound truth: a shared intent harmonizing the tangible and immaterial, is the heartbeat that sustains organizations through time.

Embracing Reality: A Call for True Innovation in Business and Governance

In the intricate web of complex systems, a prominent anomaly appears to be a new engrained defective feature—a potent «bug,» a «virus» that thrives in diverse environments, from macro-integrated systems to micro-level business operations. This anomaly champions the maximization of incentives that bolster the «status quo,» breeding mental inertia even before economic stagnation can set in.

Again, we should look a “nature”, at the “Bee Inc” operating mode where a small but vital percentage of the swarm preserves an invaluable freedom. These bees, unbound by their peers’ pollen-rich «deposits,» venture into uncharted routes, recognizing the necessity of embracing randomness and unexpected upsides to safeguard against predatory attitudes towards present resources. A pursuit of short-term financial maximization, scholars affirm, would have driven the bees to extinction over millions of years—far less time than IBM needed to plummet from the ivory peak of the tech kingdom.

Brunelleschi’s brilliance was not just in architectural prowess but in fostering a dialogue among his «collaborators.» By creating prerequisites for real-time updates and dismantling information «silos,» he thwarted disastrous inefficiencies stemming from the inevitable turf wars (Gillian Tett, the Silo Effect: The Peril of Expertise and the Promise of Breaking Down Barriers).

Both in the intricate corporate systems of sprawling multinationals as well as in SME’s realm, the bias toward «status quo«, the cautious proceeding on a path of incremental innovation prevails, mercilessly suffocating all possible bouts of genuine transformation (The Economist: Innovation beyond the comfort zone – White Paper by Équité | Dr. Daniel Langer).

True innovation requires a Copernican shift in governance, it demands the courage and honesty to acknowledge and level with the everyday reality that business has and will have to face for a very long future: a reality of radical uncertainty (Radical Uncertainty, decision-making beyond the numbers, M. King, J. Kay) and aptly encapsulated in the V.U.C. An acronym, denoting volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity (McKinsey, The 5 Trademarks of Agile Organizations)

So, what’s the antidote? It lies in embracing the messiness of reality and facing the music, possibly jazz music as advocated by Frank J. Barrett: «Say yes to the mess” acknowledging the enterprise’s inherent condition as one that is “teetering on the edge of the unknown and ready to embrace it”.

The assonance between jazz and business, delineated by management professor and jazz musician Scott, is striking. If business management is a liberal art—a marriage of discovery and knowledge, steadily honed over time (P. Drucker, The Practice of Management)—then the prevalent managerial approach appears grossly inefficient. Relying on predetermined inputs and outputs, driven by assumptions formulated in laboratories or, in the age of remote work, even kitchen dens, falls short. Od a very long mile.

In Scott’s musical analogy and Drucker’s managerial vision, management shapes power dynamics, structures value, and outlines responsibilities within the corporate landscape. To navigate the complexities of the modern business realm, an evolved approach is required: one that recognizes uncertainty as an ally, innovation as a force, and embraces reality’s messiness to usher in a transformative era of governance and business excellence.

Beyond Structure: The Unstructured Prelude to Innovation in Jazz and Business

In both the realm of jazz and business, unstructured participation within a community narrative lay the foundation for a unique camaraderie. This organic aggregation, free from rigid classifications and roles, often reminiscent of “coffee shop chill”, sparks natural conversations that then evolve into a threaded and co-created corporate narrative.

This narrative proves vital during periods of uncertainty, providing a precious compass to navigate unchartered waters. And only unchartered waters are worth navigating and exploring. Procedural shortcuts are reevaluated, morphing into bottom-up innovation. The shared narrative acts as a behavioral coagulant, enabling rapid, efficient decision-making in alignment with the ever-shifting market sentiment.

Central to this concept is the notion of «peripheral participation.» Operational notes are exchanged, deconstructed, and reconstructed among diverse roles—managers, line-workers, engineers, legal officers—all on equal footing just as it happens with a jazz band rehearsing for a session. Ego relinquishment, untethering from functional and bureaucratic labels, becomes the litmus test.

On this track, the corporate entity embarks on authentic diversification, establishing a distinctive positioning that fosters a potent, long-term competitive edge.

This edge springs from the intangible, from internal coordination, from the intent unique to that enterprise—a genetic mutation that differentiates the mere corporate entity, the ensemble of people and things neatly recorded on a ledger and, while on the other side of the moon, fully invisible to the Newtonians reductionist blinded by his own faked numerical efficiency, lays the corporate persona (The Hero and the Outlaw, M. Mark & C.S. Pearson).

This corporate persona radiates character at every consumer touchpoint, be it physical or digital, culminating in the realization of the elusive «branded experience» naturally blossoming out of that wicked experience emerging from a unique combination of people, purpose, place, and product» (Re-Engineering Retail, Doug Stephens).

From Brunelleschi’s architectural feats to Drucker’s modern management principles, resonating with retail guru D. Steven and the jazz musings of J. Scott, a common thread emerges—a herringbone arrangement of bricks, symbolizing structural support and coherence for the entire corporate framework.

This support grows proportionally as the structure expands, assimilating new functionalities and competencies that harmoniously integrate. Gone are the days of gravitational collapses caused by artificial frames and prepackaged interpretations of external reality. Instead, a path of mutual parity and dignity emerges, epitomizing the value of individual contributions as agents of action, not just mere performers free to comply and not to create. Easier said than done.

Large-scale analyses such as this one often incite skepticism, leading to the inevitable question, «…and then what?»

Practical application, the transition from theory to action, becomes a natural aspiration. The desire for tangible outcomes from complex frameworks it’s only understandable.

Beyond Conformity: Embracing the Paradoxes of Modern Commerce

And then what?

Beyond the rhetoric, lies the pursuit of something far more profound—the creation of an utterly unique, astonishingly evocative, and emotionally charged value proposition that defies prediction. This value beckons consumers to engage with the essence of a message, a full-blown philosophy, a value system, where the product or service becomes an exquisitely crafted «proxy,» a conduit for something greater. Yet, reaching this point mandates establishing a set of shared values through dialogue—ironically conducted away from the media cacophony of «buy me» shouts that saturate both traditional and digital channels.

And then what?

The organizational structure must transcend the mechanical and take on a living essence. Like a sentient entity, a company should emanate its own «humanity.» An inclination for dialogue beyond the confines of commerce becomes essential—a dialogue that fosters intimacy, co-creation, and a shared sense of purpose. Only then can the ultimate goal be achieved: the embodiment of value in the form of goods sold.

The inescapable commercial imperative compels companies to shed their bureaucratic trappings—pre-formed, cold, and externally focused entities fixated on a single metric: maximizing the economic value of production factors. This metric drives a deluge of strategic rationalizations, but can it genuinely connect with the capricious jazz of the unpredictable consumer? A company unable to internalize the market’s cutting edge, failing to orchestrate the symphony of consumer desires, will falter. It won’t sell.

And «The Big Con.» shortcuts won’t help either. (The Big Con,» Marianna Mazzucato, Rosie Collington).

Segmentation by economic «type,» a fantastical if not phantasmagorical phenomenon magically borne out of the secret formulas of a Big Con that proved perfectly ambidextrous at “infantilizing” the British public sector and at sedating the once vigorous «animal spirits» of business leaders is now collapsing under its own shortcomings well revealed, again, by dropping…sales!

Big Con, short for the global consultancy world, has crafted and sold a rigid, linear correlation between offerings quality and consumer types, a symmetrical and mechanical hinging on a segmentation of the consumers, all of us, so immanent to make Plato’s allegorical gold, silver and bronze souls pale.

However, Big Con is coming home to roost. And it was about time. If only logic and deductive numerical processes applied in the fictional world of the “focus groups” could be enough to cover the whole spectrum of commercial success we would still be short of a Sony Walkman and a Red Bull, “the worst ever tasting drink I’ve ever tried and that would not drink even if paid to”. This is the sentencing of the head of one of the most renewed agencies focusing on ..focus groups. Less focusing and more exploring are called for. Again, look at the bees. A 20 million-year-old operation should tell you something.

And then what?

A company entrenched in bureaucratic lethargy, sluggishness, and rigidity will inadvertently commit the gravest «commercial crime«: boredom as well pointed out by Remo Ruffini, the Genius of Moncler: “Difficulty is not the enemy –boring is” (Moncler’s Genius collab hit machine to extend to art, music, sports, Vogue Business).

In a world of sophisticated markets and astute consumers, slow, mechanical, and bureaucratic production cannot penetrate mobile device screens. Instead, it bounces off, as data reveals (Harvard Business Review, Branding in the Age of Social Media, by Douglas Holt).

The wisdom in the «then» is best epitomized by Gerscovich, founder of I.O.A.L., Industry Of All Nations, a pioneer in sustainable consumerism. He captures the ethos of the 3% that constitutes 40% of Farefetch’s sustainable product purchases. Gerscovich underscores a powerful truth: products and messages merely “produced” by corporate entities as opposed to the ones “created” are dismissed as “orphan” products evoking a genuine «disgust» within discerning, ethically conscious consumers, who yearn for something authentic (The Sum of All Small Things, Elizabeth Currid-Halkett).

And then what?

To forge ahead, we must glance back, embracing inventiveness and the audacity to break free from the cage of logical constraints. Courageously defying norms, Alberto Alessi’s words resonate: «transgression that pleases the common people, manifesting itself in objects that break the rules while keeping one foot in the market.» This original ethos finds resonance in Aurelio Zanotta’s insights: «We must present the public with a production that has specific functions but also has innovative and emotional qualities.»

The reinvigoration of «Made in Italy,» which is experiencing a decline in one of its key markets, the USA, (Daniel Langer, Why Luxury Brands Must Think Differently in 2023, Jing Daily), can harmonize with a long-standing tradition of unmatched skills and unconstrained thinking. This tradition, unshackled from market concerns and disdainful of «focus groups,» has the potential to redefine today’s «monodirectional» capitalism escaping the compressing metrics of the financial trinity of ROE, ROA, and ROI.

In fact, Made in Italy’s evolution hinges on a newly found internal coherence, shared among all stakeholders. Failing to evolve as a cohesive system, neglecting the organizational foundations that could restore man as «homo faber» rather than a mere «animal laborers,» is more than a mere failure to meet «G» in «ESG.» Its forfeiting equals recoiling from a competitive footing and from the opportunity to distinguish oneself based on the most relevant market-driven criteria.

A newfound common ambition, an awakening to the indispensability of the «Italian system,» could propel the Nation Brand to not only identify but assert itself as a «leader» in shaping the economy. The aspiration is a paradigm shift toward stakeholder capitalism, as envisioned by Lorenzo Bertelli: «The dream is to move towards stakeholder capitalism» (Could Made in Italy become synonymous with sustainability? Vogue Business).

And then what?

Let’s conclude with wisdom from Professor Aswath Damodaran, a finance luminary renowned for corporate valuation strategies. His «Investing and Valuation Lessons from the Renaissance» delineates three guiding principles for financial efficiency and analysis. These principles include the revival of «faith» and coherence as vital resources, the embrace of humility as a structural facet of economic efficiency, and the perpetual amalgamation of art and science in harmony with Peter Drucker’s bedrock management principle.

Marco Gianni

Business Strategist–

Il dottor Marco Gianni è un professionista esperto con una vasta esperienza nel campo legale e finanziario. Ha lavorato come avvocato presso lo studio Legale del Professor Bernini, già ministro degli esteri, concentrandosi sul contenzioso commerciale internazionale. Successivamente, ha ampliato le sue competenze internazionali lavorando come manager dello studio legale del Professor Sammarco a Miami, focalizzandosi sul diritto tributario internazionale.

La sua carriera nel settore finanziario è iniziata con esperienze presso istituti bancari in luoghi prestigiosi come Lussemburgo, Montecarlo e Zurigo. In seguito, si è trasferito a Londra, dove ha ricoperto il ruolo di manager presso il principale operatore di cambi della City per il mercato italiano.

Oggi, il dottor Marco Gianni si dedica alla consulenza strategica nel settore del lusso, collaborando con una delle più importanti agenzie del settore. La sua vasta esperienza professionale e la sua conoscenza del diritto internazionale e delle dinamiche finanziarie lo rendono un consulente affidabile per le aziende che operano nel mondo del lusso.